Reflections on Joy and Parenting

It's been two years since we started Joyful Parenting San Francisco! Some thoughts about the meaning of joyful parenting, and holding to joy as a compass rather than a pressure.

But first: it’s the last weekend to visit the Ruth Asawa retrospective at SF MOMA. Ruth Asawa was a beloved San Franciscan artist, known for her fountains and intricate hanging wire sculptures. She was also a mother of six, and insisted on the integration of art and life with children. She took great pride in the everyday work of care, calling it her privilege. One of the wall texts reads:

“I’ve always had my studio in the house because I wanted my children to understand what I do and I wanted to be there if they needed me—or a peanut butter sandwich.”

She has been the subject of many great books on art and motherhood in recent years, including Ruth Asawa and the Artist-Mother at Midcentury and Everything She Touched. She eschews the traditional binaries between arts and crafts, career, parenting and civic life. There’s a lot to learn from artists and writers who embraced parenting as a creative force. Maybe more on that later.

To celebrate two years of Joyful Parenting SF, we wanted to revisit the core ideas and concerns that got us started. Parents’ stress and unhappiness is often attributed to lack of support, in particular public support for childcare. On the other hand, despite their access to free or cheap and extensive childcare, French parents feel deeply unfulfilled and that children impede their freedom, more than in any other Western countries surveyed. So it’s a little bit more complicated than that.

How we Talk about Happiness and Parenting

We are not trying to keep up with the parenting discourse because it’s a constantly shifting minefield, but it was hard to miss the reactions to Chappell Roan declaring that she doesn’t know any happy parents. (Yes, that was back in April, it took us a while between first draft and publication). Conservatives roared against that statement, while progressives welcomed it, with the latter emphasizing we need a much stronger safety net and supportive infrastructure for parents to feel less stressed and therefore happier. This is something we have written about before, exploring the benefits of cooperative childcare, how to do things we love with our kids, and why we really do need to be less stressed.

Jennifer Senior’s book All Joy No Fun: The Paradox of Modern Parenthood, which argues that although children bring us existential joy, they do not bring us fun or warm feelings on a day-to-day basis, which kind of implies we just have to get along with it. Elissa Strauss (author of When You Care: the Unexpected Magic of Caring for Others) responded to the Chappell Roan controversy by reminding us that joy and happiness might be the wrong framing altogether to understand and improve our experiences of parenthood. She invites instead to focus on what is a meaningful and rich life experience, which will necessarily also be tiring or frustrating sometimes at the very least.

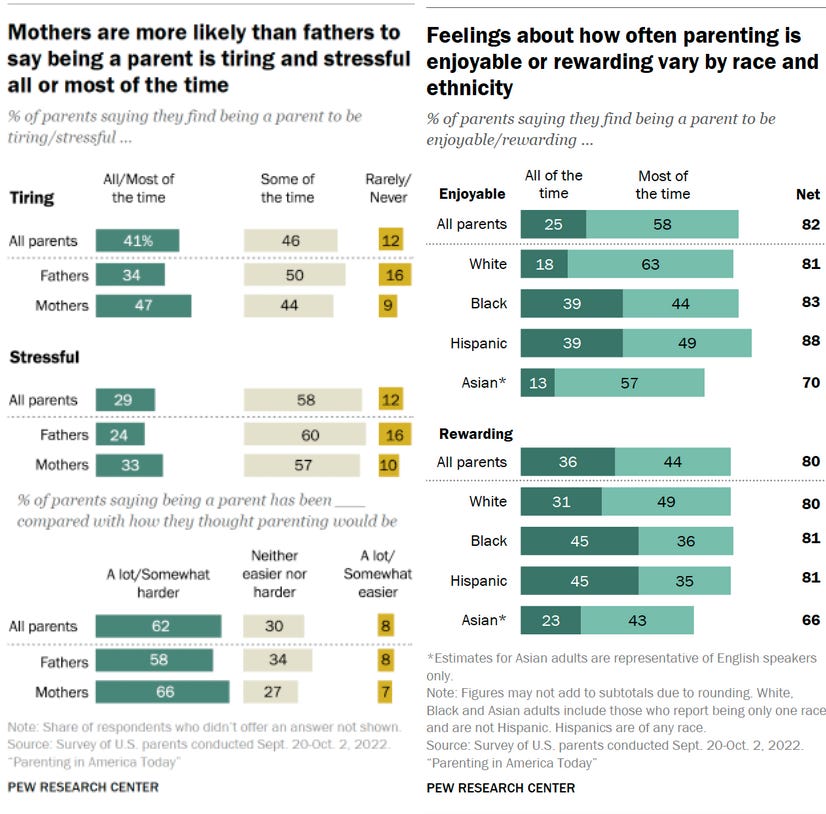

Of course we need to improve parents’ circumstances. One of our motivations for starting Joyful Parenting was a Pew Research study on disparities in the enjoyment of parenting: Moms are more likely than dads to say that they find parenting tiring or stressful all or most of the time, and Asian Americans tend to find less enjoyment and fulfillment from parenting compared to people of other ethnicities. The report suggests this might be due to higher stress levels over children’s outcomes and the pressures of intensive parenting. Similarly, mothers are more likely than fathers to find parenting stressful and tiring than fathers.

Should we Expect Joy, Fun, Happiness, Nothing?

So, disparities in the enjoyment of parenting point to social inequalities; but perhaps focusing on happiness and joy in parenting is the wrong way to go about it altogether, just one more pressure preventing us from seeing the whole picture.

We do both strongly believe in joy as a compass; that lack of joy and happiness points us to something that we could perhaps do differently. But we differ significantly in our parenting approaches. I chose full-time parenthood for 18 months when my son was born, and it was a magical period where I made art, incredible friends, volunteered in lots of places and was out and about with my kid all day. I’m grateful for how that almost constant companionship changed me and for the depth it gave to our relationship. I strongly believed it made me a better parent. Now that I’m back at work, in a job I deeply love, I still can’t imagine not picking him up at 3pm - I just cherish those long afternoon hours. But it did come to the expense of the kind of other ambitions that would consume that time.

Ruth on the other hand prefers a split childcare schedule. There are many ways to feel fulfilled by parenthood, and to find joy and happiness in its daily exercise.

But what if you are unhappy as a parent? When we first discussed formalizing the organizing we were doing, Ruth and I named it “Kid-Friendly SF”, as we noticed that care feels tiring and stressful because we lack welcoming public spaces. But kid-friendly doesn’t begin to encompass the changes needed. Playgrounds are kid-friendly (and they are families’ third spaces, and we love them!) but they are somewhat limited when you want to do other things with your kids than hang out with parents. I do often use that time to read, write and draw, but it’s also really nice to be welcome in a café, in creative spaces, at civic and political meetings and conferences. Often it's not about the space at all - it's about a societal attitude towards parenting as an activity separate from regular civic and social life, isolating parents and depriving them of the examples and time they would need to change things.

A Literary Tangent: the Artist-Mother of Nightbitch

This is well illustrated by Nightbitch, the story of an artist mother staying at home because childcare costs more than her salary at an art non-profit. In the movie she appears serene and happy, a varnish broken by internal monologues about how much she hates being a mother. In the book, she comes across as overwhelmed, struggling to parent calmly. In both, she finds balance when she… transforms into a dog. She begins embracing animality and play. It changes how she engages and plays with her kid, embracing the chaos regardless of what others may say. It gives her energy - and she paradoxically starts engaging in all the mommy-and-me activities she previously despised. She also starts claiming time and space for her artistic practice, her husband stepping up to take care of their son.

I won’t spoil the ending for you, but I think it makes some great points.

The dad is very clearly clueless and withdrawn from the responsibilities of parenting until she makes him step up: gender equality in parenting is important for mothers to thrive. She embraces “intensive parenting,” engaging in a rigorous schedule of structured enrichment activities, and advocates for messy. She makes time for her art but her daily life largely looks the same: it’s her mindset towards toddlerhood and that connection that changes. She’s such a great mom… and she works so much for it, literally reshaping herself to make it happen.

So What Do we Do?

This was a very uncomfortable read and conclusion - it just seems far easier to outsource the work of (child)care to paid workers as much as we can. We do know that building a community to find support and connection also requires energy and commitment. But when I hear people painting France as some sort of utopia where parents are better supported because they spend less time with their kids than before, I cringe. First because, as mentioned, French parents feel deeply unfulfilled and that children impede their freedom, more than in any other European countries. To keep childcare cheap, France relies on workers who are often poorly treated, with a high ratio of children to caregivers. Early childhood caregivers are often women and immigrants, who carry both physical demands and class-based power disparities inherent in their line of work — although at least they make solid middle class wages when they work full time, which is definitely not the case in the US. In other words, the time we spend with our children isn’t as much of a problem as the fact that it is little valued by society, and made harder than it should be and confined in the home.

I wish we were better supported in finding out what works for us, how we can grow in parenting and in caring, and focused on making paid work less overwhelming and demanding so that we are not losing ourselves in the process. This is far from a novel insight: Adrienne Rich’s Of Woman Born published in 1976 already points to that double bind.

There are different propositions to fix this. One is to enable and encourage part-time work for everyone to achieve better balance. For instance, Ruth was able to work part time at her tech company day job as part of a special leave that was made available for caregivers during the beginning of the pandemic1. Another is to make some logistics easier with colocated childcare centers and offices. Patagonia provides on-site child care as an employee benefit, as do some hospitals as their workers need coverage at odd hours. More generally, it doesn’t seem that we will make much progress if we don’t value time spent parenting and with dependents (children, but also elders) more.

Meanwhile, Ruth is working on a much less serious post with lots of suggestions on how you can stop trying so hard as a parent – stay tuned :)

That benefit is no longer available due to lack of use. We think that maybe workers who wanted to work part-time preferred to try to work less while getting paid their regular salary, instead of having a formal part-time agreement.